INTRODUCTION

Oral health is an important component of general health and a determinant factor for quality of life. Despite the recognition of oral health as a human right, individuals throughout the world, particularly the poor and socially disadvantaged in developing countries, suffer greatly from oral disease.1 Among the conditions they face are caries, gingivitis and periodontal disease, tooth loss, oral cancer, HIV-AIDS-related oral disease, facial gangrene (Noma), dental erosion, dental trauma, and dental fluorosis.1-3 Worldwide, oral disease is the 4rth most expensive diseases to treat; Dental caries affects most adults and 60-90% of school children, leading to millions of lost school days each year, and it remains one of the most common chronic diseases; periodontitis is a major cause of tooth loss in adults globally and oral cancer is the eighth most common cancer and most costly cancer to treat. With oral infection has been associated with issues ranging from pre-term birth and low birth weight to heart diseases, it may be an important contributing factor of several preventable disease.4

The burden of oral disease may be linked to any of these factors like poverty, illiteracy, poor oral hygiene, lack of oral health education.5 Apart from this, persistent inequalities in access to oral health care with inadequate dental materials, drugs, instruments, and equipment are equally responsible.6, 7 Although there are more than one million practicing dentists, worldwide, their unequal geographic distribution results in oversupply in some wealthy urban areas. Globally, roughly only 60% of the population worldwide enjoys access to proper oral health care, with coverage ranging from 21.2% in Burkino Faso to 94.3% in Slovakia. Between countries the density of qualified dentists varies from one dentist per 560 people in Crotia to one dentist per 1278,446 people in Ethopia; and the distribution within the counties strongly varies.4

In view of the burden of oral diseases, there has been a strong international aid response to public health emergencies and oral health disparities in developing countries.8, 9 Many of the dental nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and volunteers have contributed to remedying global oral health disparities.10, 11 The activities of these groups included service provision, education and training, technical assistance and community development. The major limitations were inadequate services and non-sustainability.12

The WHO Collaborating Centre at the University of Nijmegen in the Netherlands has worked within primary oral health care principles to create an affordable and sustainable community service called the basic package of oral care (BPOC).13 The BPOC is designed to work with minimum resources for maximum effect and does not require a dental drill or electricity. The BPOC can be tailored specifically to meet the needs of a community. Most significant is the fact that a dentist trained in BPOC can train local ancillary medical and dental personnel to become BPOC-proficient.14 These local non-dentist BPOC-trained individuals can then become the primary resource for oral health promotion.

This community service is not a formally recognized competency for a general dentist in most of the countries in the world including North America. The revised competencies for the predoctoral dental school curriculum endorsed in March 2008 by the American Dental Education Association (ADEA) are intended to define the entry- level professional capacities of the general dentist. However, this document neither has any mention of community service, nor regarding provision of care to the underserved communities or populations under the domain of professionalism.15

However, Global oral health course has been introduced in some developed countries of the world, but the same has not been introduced in india - one of the nations which has highest number of dental institutions in the world. So, the present study was conducted to investigate the outlook of dental students about global oral health issues in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present cross sectional questionnaire study was conducted among the dental students in the H.P Government Dental College, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India. Ethical approval to conduct the survey was obtained from the Head of the Institution i.e. Government Dental College and Hospital, Shimla.

The dental curriculum in India consists of 5 years of education of which 2 years course is dedicated to basic (Preclinical) education and 3 years to clinical education. So, only the students exposed to clinical dental education were included in the study. All the 3rd year, 4rth year and interns were informed about the study during March 2014. There were total of 94 students in 3rd year, 4rth year and internship.

A self-administrated questionnaire consisting of 15 close-ended items was used for data col-lection. The questionnaire was distributed to 3rd and 4rth year students after their scheduled lecture. The questionnaires were distributed to interns in their respective departments. All the students were given fifteen minutes to fill the questionnaire before collecting back. The questionnaire was a modification of the global oral health information questionnaire (GOHIQ). The original GOHIQ consisted of 5 sets of questions but the present questionnaire was modified to 15 questions to broaden the scope.16 Additional questions were regarding their present knowledge of global oral health status, about international volunteerism and ethics and development of oral health goals.

The validity of the survey questions can be assumed given that the questions had been used previously.16-18 The questionnaire was pretested by conducting a pilot study with 5 students from each year in order to assure that the students understood the questions and were able to answer them without help.

The data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version 16 for windows).

RESULTS

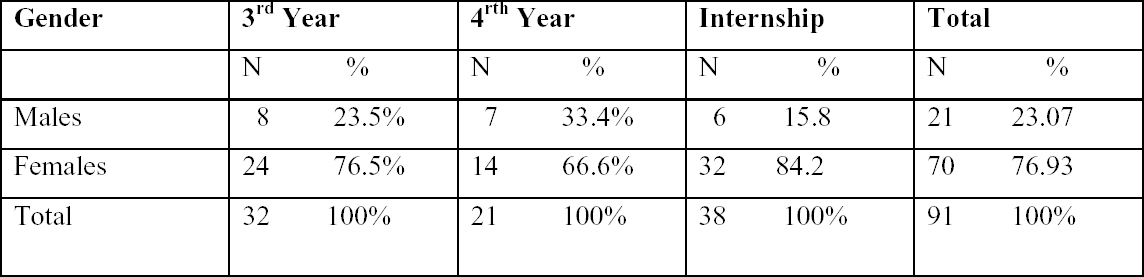

All together there were 96 students in 3rd year, 4rth year and internship. Out of 96 students 91 responded which means the response rate was 94.7%. Out of 91 responded students there were 21(23.07) males and 70(76.9) females. The distribution of subjects is shown in table 1.

|

Table 1: Distribution of subjects according to study year.

Click here to view |

|

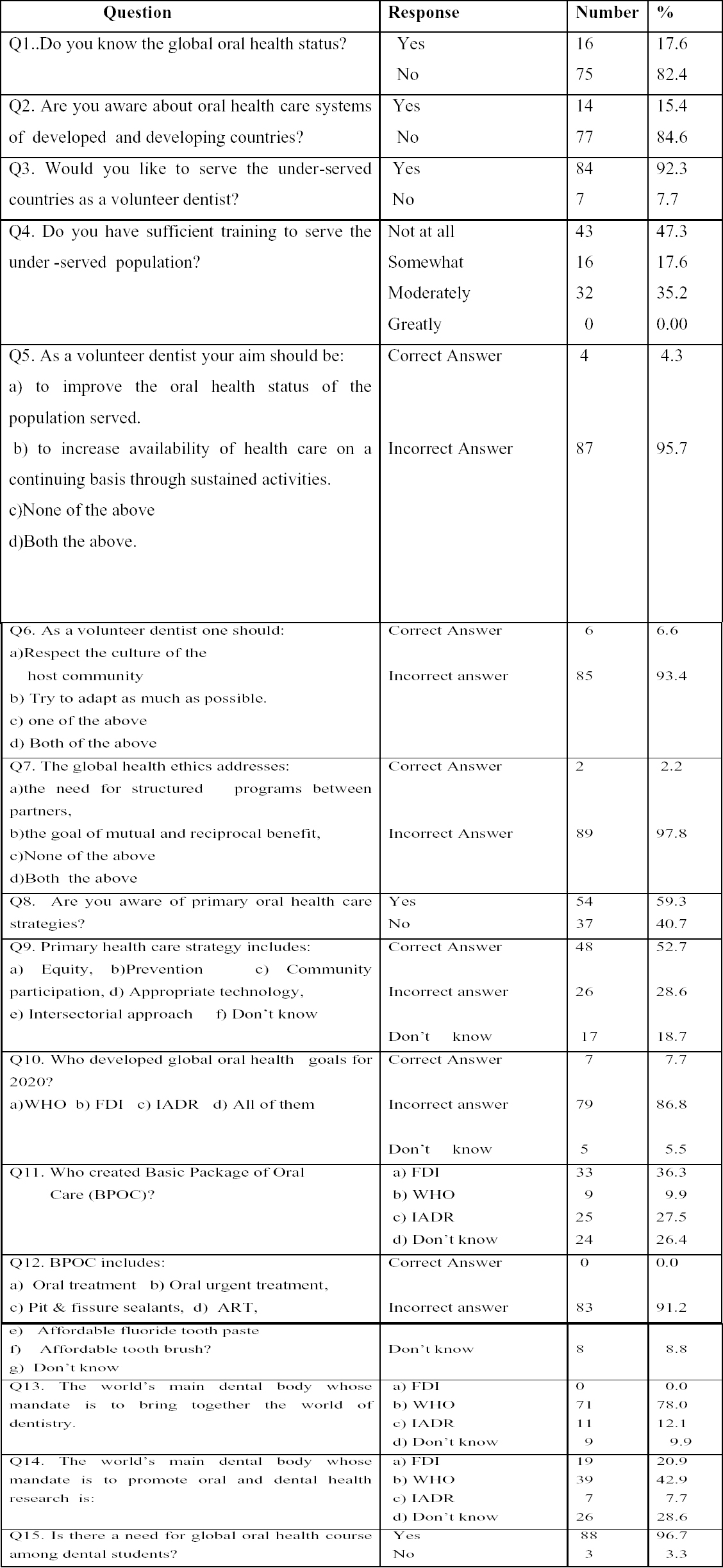

Table 2: Response to Global oral health information questionnaire:

Click here to view |

Most of the students 82.4% (75) reported that they were not aware about global oral health status and 84.6% (77) reported that were not aware about oral health care systems of developed and developing countries. 92.3% (84) percent of surveyed students stated that they would consider volunteering their dental skills and expertise as a senior dental student or future dentist in an international setting or developing country, whereas 7.7% (7) stated that they would not. 47.2% (43) of the surveyed students reported that they felt that the dental education had “not at all” prepared them to serve the underserved population, 17.7%(16) reported that they were somewhat prepared, 35.1%(32) reported that they were moderately prepared and no one reported that he was greatly prepared.

When asked about the aims of a volunteer dentist 60.4% (55) reported “to improve the oral health status of the population served”; 35.1% (32) reported “to increase availability of health care on a continuing basis through sustained activities “and 4.3% (4) reported the option “both the above.”

When asked about the cultural competence of dentists, 64.8% (59) reported “to respect the culture of host community; 28.7% (26) reported “try to adapt” and 6.5% (6) reported “both the above.”For the question on global health ethics, 8.6% (8) correctly reported the option “ both the above” 52.7% (48) students could correctly identify equity, community participation, appropriate technology and inter-sectoral approach as components of primary health care. Only 9.8% (9) of the surveyed students were able to identify that basic package of oral health care (BPOC) was created by World Health Organization. None of the surveyed students could correctly answer the question about “the three components of BPOC” as OUT (oral urgent treatment), AFT (Affordable Fluoride tooth paste, and ART (Atraumatic Restorative Treatment).

None of the surveyed students could correctly identify FDI as the world’s main dental/oral health NGO whose mandate is to ’bring together the world of dentistry. Only 7.7% (7) students could report correctly IADR as the world’s main dental body whose mandate is to promote dental and oral health research.

When asked for need on global oral health course 96.7% (88) of the surveyed students reported the need for global oral health course.

DISCUSSION

All over the world, population growth and ageing have led to an increasing need for oral healthcare. Furthermore, a gradual increase in awareness as well as mass media exposure has led to an increased demand for oral health. At present, neither the need nor demand is fully met on a global level, despite the fact that oral health is a basic right and its contribution is fundamental to a good quality of life and overall health.4

So, the time is now right for developing a new model for oral health care, by shifting the focus of our model from (i) a traditionally curative, mostly pathogenic model to a more salutogenic approach, which concentrates on prevention and promotion of good oral health and (ii) from a rather exclusive to a more inclusive approach, which takes into consideration all the stakeholders who can participate in improving the oral health of the public, we will be able to position our profession at the forefront of a global movement towards optimised health through good oral health.

To better equip members of the oral healthcare workforce for the challenges at present we need to consider some modification in our educational curricula to take into account a stronger focus on prevention of oral disease in communities or vulnerable populations.

In the present study, 82.4% reported that they were not aware about global oral health status and 84.6% reported that were not aware about oral health care systems of developed and developing countries which is slightly less than 99.2% as reported by Singh A among dental students in central India.17 92.3% percent of surveyed students stated that they would consider volunteering their dental skills and expertise as a senior dental student or future dentist in an international setting or developing country which is in line with the findings by Karim A (84%), Abhinav S (87%) and Omoigberai BB(100%).16-18 47.2% of the surveyed students reported that they felt that the dental education had “not at all” prepared them to serve the underserved population.

When asked about the aims of a volunteer dentist, 4.3% could rightly answer “to improve the oral health status of the population served” and “to increase availability of health care on a continuing basis through sustained activities. Similarly only 6.5 % of the students could correctly answer question about cultural aspects on international health. The question on global health ethics was correctly answered by 8.6%.

The present study showed that 9.8% of the surveyed students identified that basic package of oral health care was created by World Health Organization which was less than as reported by Singh A(27%) and Omoigberai BB(20.5%) but higher than as reported by Karim A(0%).16-18 None of the surveyed students could correctly answer the question about “the three components of BPOC” as OUT, AFT, and ART which is in line with Karim A and Omoigberai BB.

In 1982, World Dental Federation (FDI) and WHO developed the global goal for oral health for the year 2000. About a decade ago WHO, jointly with the Federation Dentaire Internationale (FDI) and the International Association for Dental Research (IADR), formulated goals for oral health by the year 2020. These specific goals may assist in the development of effective oral health programs, targeted to improve the health of those people most in need of care.19-21 In the present study no one could recognize FDI as the world’s main dental/oral health NGO whose mandate is to ’bring together the world of dentistry as was also reported by Karim A.16 Only 7.7% students could report correctly IADR as the world’s main dental body whose mandate is to promote dental and oral health research which is somewhat similar to the findings of Omoigberai BB.18

The results of the study suggest that the majority of the surveyed dental students at this dental school expressed a desire to volunteer their professional services in international settings. However, none of the surveyed students knew about WHO’s BPOC or FDI’s role in global oral health. This means there is a gap between global oral health policy and interventions set out by WHO and FDI and awareness of this policy and global oral health issues among dental students in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India.

Hence creating a predoctoral global oral health course that includes the principles of POHC and BPOC, at all levels could reinforce the concept that care to the underserved is integral to the profession and it is an ethical responsibility. Instilling a public purpose in dental students is as important as teaching them about the newest clinical techniques or latest high tech dental software. A sense of awareness can be created that oral health education, promotion, and service delivery exist in unique parallel formulas that can be applied depending on the circumstances.22 As such, global oral health education teaches the value of alternatives and does not cripple students to believe that there is only one ideal treatment modality for all situations. This will enable students as future dental professionals to feel confident and skillful regardless of their environment; it may even inspire some to become international dental volunteers, dental NGO leaders, or oral health policy advocates. Educating students about global oral health issues includes them in the reality of global oral health disparities and facilitates the belief that they can affect change within and beyond their immediate community.23, 24

Encouraging results have been found after a curriculum change in Peru and Vetnam.25, 26 Such programs challenge dental students to value dental public health issues and provide a realistic understanding of prevailing oral health problems faced by the international community. So it is hereby recommended to develop a systematic curriculum for global oral health course in dental schools of both developed and developing countries. The curriculum elements could include global burden of oral diseases, oral health care delivery systems of industrialized and emerging economies, primary oral health care strategies, the role of WHO and FDI in international health, the role of humanitarian organizations and global dental volunteers, BPOC as a competent form of oral health care delivery, dental ethics, with topics on sustainability, global health ethics, and addressing the needs of under- served populations, and cultural competence in addressing international oral health issues.

CONCLUSION

So, it can be concluded from the present study, that the outlook about global oral health issues among dental students in Shimla is low. All the students expressed a desire to volunteer their professional services in international settings. However, few students knew about the WHO and FDI global goal for oral health as well as the role of IADR and FDI on global oral health. None of the student was able to identify correctly the three components of BPOC. The results suggest that there is a gap between global oral health policy and interventions set out by WHO and FDI and awareness of this policy, interventions and global oral health issues among dental students in Shimla, India.