INTRODUCTION

The maxillary canines are the commonlyimpacted teeth in the human dentition next to thethird molars. Impaction of mandibular canines isquite rare in comparison to maxillary canines asdescribed by Rohrer, who concluded that impactedcanines are 20 times more frequent in maxilla thanin the mandible.1 In few instances, the mandibularcanines have been found to have migrated acrossthe midline to the other side of the mandible andare described as being transmigrated. In cases wherethese teeth tend to erupt, they are usuallytransposed.

Transmigration of a tooth, in general refers tothe event of migration of a tooth away from its siteof origin. As is evident from the literature, varyingdefinitions have been attributed to thetransmigration of mandibular canine depending onthe status of the affected tooth in relation to themidline.2-4

Numerous theories speculating the aetiologyhave been put forth but none of which do accuratelydefine the cause of this unique phenomenon. Theyinclude heredity, abnormal displacement of thedental lamina in the embryonic life, axial inclinationof erupting canines, retention or premature loss ofdeciduous canine, inadequate eruption space, supernumerary teeth, excessive length of crown, endocrine disorders, trauma, diet and intrauterinedefects.5-9

The scope for treatment of these transmigratedcanines is very limited. The treatment optionsinclude preventive and interceptive treatment, surgical exposure and orthodontic treatment, autotransplantation, surgical removal andradiographic monitoring.10-14

The unpredictably unique manifestation ofthese canines renders the treatment difficult if notimpossible. Each treatment possibility presents withits own merits and demerits. The literature doesn’tgive any insight into the intricacies of the treatmenttechniques. The purpose of this article is to discussthe possible clinical implications while treating thetransmigration. Four cases of transmigration arepresented in this context.

CASE REPORTS

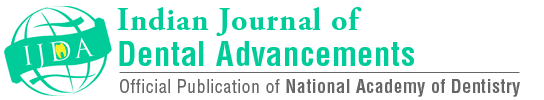

Case 1: A 16 year old male patient reportedwith the chief complaint of forwardly placed upperfront teeth (Figure 1 and 2). Medical history wasnon contributory. The patient had a dental historyof undergoing orthodontic treatment previouslywhich he discontinued midway. Clinicalexamination revealed that all permanent teeth haderupted except the two mandibular canines andmandibular left third molar. The patient had aAngle’s Class II division 1 malocclusion with a 100%deep bite, an overjet of 10 mm and posterior scissorbite. The right lateral incisor had a talon’s cusp. Thepanoramic radiograph showed the mandibular rightand left canines lying horizontally beneath theapices of mandibular anterior teeth. The crowns ofthe impacted canines were pointing towards thecontra-lateral mental foramina (Figure 3). Thelateral cephalogram depicted a small radiopaquemass in the symphysis region (Figure 4). Nopathologic finding was associated with thetransmigrated teeth. The mandibular left thirdmolar was horizontally impacted.

|

Figure 1: Extra-oral frontal view of case 1.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 2: Extra-oral frontal smiling view of case 1.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 3: OPG showing transmigrated canines impacted horizontally in the midline of case 1.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 4: Lateral Cephalogram showing the transmigrated canines at the symphysis as a radiopaque mass of case 1.

Click here to view |

Case 2: Clinical examination of a 19 year oldmale patient who presented with the chief complaintof irregularly placed lower front teeth revealed classI molar relation and a retained mandibular leftdeciduous canine. The permanent left canine wasupright and erupted in the midline, labial to themandibular right central incisor (Figure 5 and 6). No pathologic finding was associated with thetransmigrated tooth.

|

Figure 5: Intra-oral photograph showing transmigrated permanent left mandibular canine of case 2.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 6: OPG showing 33 overlapping the image of 41 in case 2.

Click here to view |

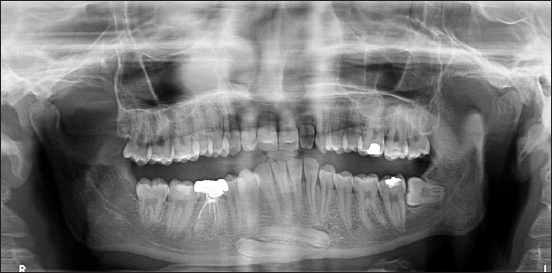

Case 3: A 30 year old male patient presentedwith the chief complaint of missing upper frontteeth. On clinical examination, he was found to havea class II molar relation, 100% deep bite, scissor biteon left side, congenitally missing maxillary lateralincisors and over retained mandibular rightdeciduous canine (Figure 7). Panoramic radiographrevealed obliquely impacted mandibular rightpermanent canine at the midline (Figure 8). Nopathologic finding was associated with thetransmigrated tooth

|

Figure 7: Intra-oral frontal view of case 3.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 8: OPG showing obliquely placed 43 with the crown crossing the mandibular midline in case 3.

Click here to view |

Case 4: A 15 year old male patient presentedwith the chief complaint of irregularly placed lowerfront teeth. On clinical examination, he had a classI molar relation, transmigrated and transposedmandibular canines. The left permanent mandibularcanine had erupted in the midline, with the otherpermanent canine lying adjacent to it on the rightside (Figure 9 and 10). In the strict sense, the rightcanine couldn’t be termed as transmigrated. Nopathologic finding was associated with thetransmigrated tooth.

|

Figure 9: Intra-oral view of the mandibular canines lying adjacent to each other in case 4.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 10: Mandibular occlusal view of case 4.

Click here to view |

DISCUSSION

Mupparapu classified mandibular caninetransmigration depending on its path of deviationinto five types. Type 1: Canine positioned mesio-angularly across the midline within the jaw bone, labial or lingual to anterior teeth, and the crownportion of the tooth crossing the midline (45.6%). Type 2: Canine horizontally impacted near theinferior border of the mandible below the apices of the incisors (20%). Type 3: Canine erupting eithermesial or distal to the opposite canine (14%). Type4: Canine horizontally impacted near the inferiorborder of the mandible below the apices of eitherpremolars or molars on the opposite side (17%). Type5: Canine positioned vertically in the midline (thelong axis of the tooth crossing the midline)irrespective of eruption status (1.5%).15

The first case reported in this paper belongedto Mupparapu classification type 2, whose positionis unfavourable to attempt orthodontic traction(Figure 3). Surgical removal leaves a temporarylarge bony defect and is associated with risks ofiatrogenic fracture of the mandible and injury to theelements of mandibular canal. Since the teeth areasymptomatic, periodic radiographic monitoring isbeing carried out in conjunction with thecomprehensive orthodontic treatment that thepatient is receiving for his malocclusion. Furthermore, the significance of periodicobservation is emphasized by the fact that theaffected canines lie in close proximity to the roots ofmandibular incisors because of which, duringorthodontic tooth movement, there may bepossibilities of root resorption of mandibular incisorsand/or pathologic changes in relation to the sleepingcanines. As the patient presents with 100% deepbite, the possible treatment options are intrusion ofthe maxillary or mandibular incisors. Intrusion ofmaxillary incisors could be carried out but at theexpense of soft tissue balance since the patient haszero incisor exposure at rest and the intrusion ofmandibular incisors is complicated by the precariouslocation of the transmigrated canines.

The second case belongs to the Mupparapuclassification type 5. This transmigration is welltreated by extraction of 33. Space discrepancyrenders the alignment of the canine quite difficult. Orthodontic alignment, if possible, has to be donefollowing carefully planned extractions. However, this mode of treatment seems to be cumbersomegiven the ectopic position of the transmigratedcanine which in itself warrants its extraction. Furthermore, since the canine needs to be alignedat the midline itself, transmigrated canine crownshould be sequentially contoured to resemblemandibular central incisor. Conversion of canineinto an incisor requires removal of a substantialamount of crown structure which may necessitateintentional root canal therapy followed by a crown. Another major drawback is that a canine guidedocclusion cannot be established. Also, the canine isvulnerable for root dehiscence because of the narrowdistance between the labial and lingual corticalplate. In a similar case treated by Brezniak, Yehudaand Shapira gingival recession was found on thelabial side of the treated canine.16

The third case belongs to the Mupparapuclassification type 1. The root of the affected caninelies in a favourable position but the success oforthodontic traction to get the tooth into the arch isquestionable due to two factors. Firstly the exactposition of the canine in the sagittal plane needs tobe determined. A labially positioned tooth isamenable for surgical exposure and bondingattachments. Secondly the proximity of thetransmigrated canine to the roots of lower centralincisors creates complications as discussed earlier. Surgical removal may be considered.

The fourth case belongs to the Mupparapuclassification type 5. According to the classification, the mandibular left canine alone can be termed astransmigrated. The migration of mandibular rightcanine seems to have been obstructed by the leftcanine. Considering the space deficiency in themandibular arch, extraction of both the canines wascarried out and the first premolars were convertedinto canines. In a scenario where there was adequatespace in the lower arch, orthodontic traction of theright canine could have been an option since it waspositioned at a shorter distance without actuallyhaving crossed the midline. The left canine couldhave been treated similar to case number 2. However, this approach would require longertreatment duration and lighter forces as the toothis moved through dense cortical bone.

CONCLUSION

In recent years, many cases of transmigrationof mandibular canines have been documented. Thecorrective treatment of these canines is debatableand quite challenging. When the impacted teetharen’t removed, care has to be taken not to inducepathologic changes. Maintaining the health of theperiodontium of the transmigrated tooth as well asthe adjacent teeth is critical while attemptingorthodontic traction. Root torqueing in specific casesshould be planned prior to initiation of orthodontictreatment to place the root in trabecular bone. Iatrogenic damage can be best avoided by carefultreatment planning with due consideration to theclinical implications of the particular case. Thoughearly detection and treatment is suggested in theliterature, evidence is lacking in support ofinterceptive measures.