INTRODUCTION

The word tobacco was initially used to denote aY - shaped piece of cone or pipe called Tobago ortoba caused by Mexican Indians to inhale powderedleaves of a plant. Later the plant came to be knownby the name of the device, as “tobacco”.1 The nicotinefound in substantial amounts in tobacco products iswidely considered to be a powerful addicting drug, so much so that its addictive processes and potentialhave been equated with heroine, morphine andcocaine. Its rapid absorption through the lungs ofcigarette smokers is widely accepted, but it’s equallyready absorption through the oral mucosa under thealkaline conditions is less publicized.

Among 400 million individuals aged 15yrs and over in India, 47% use tobacco in one form or theother. Some 72% of tobacco users smoke bidis, 12% smoke cigarettes, 16% use smokeless tobacco. Of 250million kg tobacco cleared for domestic consumptionin India, 86% is used for smoking and 14% insmokeless form.1 Tobacco is used in a variety offorms, mostly as smoked, but many populations usesmokeless tobacco, which comes in two main forms; snuff (finely ground or cut tobacco leaves that canbe dry or moist, loose or portion packed in sachets)and chewing tobacco (loose leaf, inpouches of tobaccoleaves, plug or twist form).2

Harmful substances in tobacco

Smoked and smokeless tobacco containsnicotine as an important constituent. Thousands ofchemical compounds in tobacco act not only asirritants and toxins but carcinogens. Over 300 carcinogens have been identified in tobacco smokeor in its water soluble components which can be expected to leach into saliva. The importantcarcinogens are listed below:

-

• aromatic hydrocarbons,

-

• benzopyrene and tobacco specificnitrosamines,

-

• N-nitrosononicotine (NNN),

-

• nitrosopyrollidine (NYPR),

-

• nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) and

-

• 4-(methyl nitrosamine)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone(NNK).

Benzopyrene is a powerful carcinogen whichaccounts to about 20-40mg per cigarette. The mainstream smoke of a cigarette contains 310mg of NNNand 150ng of NNK. These agents act locally onkeratinocytes, stem cells and are absorbed and actin many other tissues in the body.3

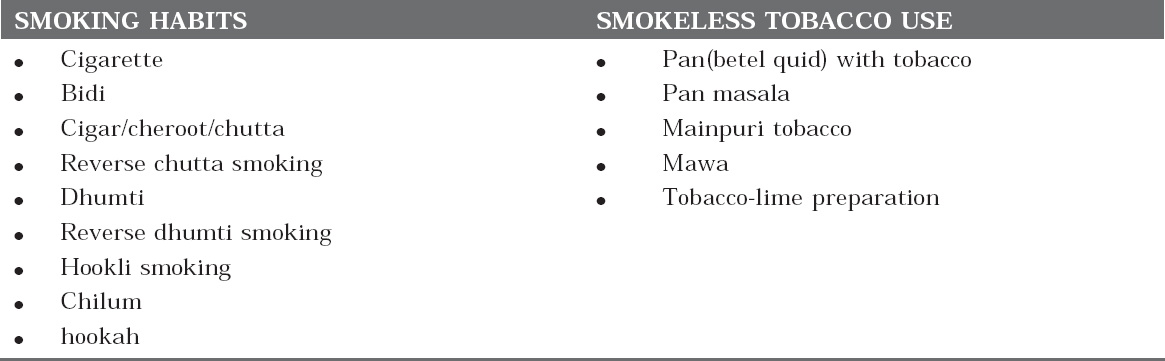

Tobacco Related Habits (Table 1)

|

Table 1: Tobacco related habits

Click here to view |

Smoked and smokeless tobacco forms are usedin different fashions referred to as habits (Figure 1).1

|

Figure 1: Tobacco related habits (A) Chilums (B) Betel quid (C)Beedi (D) Dhumti(E) Mawa preparation(F) Hookah(G) Pan masalacontaining tobacco (H) Reverse smoking (I) Cigar (J) Hookli smoker (From Fali S. Mehta, Hamner JE. Tobacco related oral mucosallesions and conditions in India. A guide for dental students, dentists and physicians. Basic dental research unit. Tata institute offundamental research.1993, Bombay.)

Click here to view |

Oral mucosal response

Tobacco consumption is positively correlatedwith accumulation of DNA damage. Exposure totobacco-related chemical carcinogens could providedirect damaging effects on the cellular DNA in thehuman oral cavity. Tobacco constituents effects theoral mucosa in different ways finally leading tocancer through carcinogenesis.4

Tobacco products act as chemical carcinogensand participate in chemical carcinogenesis. First, the initiating carcinogens in tobacco which act asreactive electrophiles (having electron deficientatoms) react with nucleophilic (electron rich) sitesin the cell. Their targets are DNA, RNA and proteinsand in some cases may cause cell death. Initiationinflicts nonlethal damage on the DNA that cannotbe repaired. The mutated cell then passes on theDNA lesions to its daughter cells.4 Initiatingcarcinogens are generally of two types. They aredirect and indirect acting agents.5

Tobacco constituents are mainly indirect actingagents. There are some metabolic pathways whichlead to inactivation of procarcinogen or itsderivatives. Thus the carcinogenic potency of achemical is determined not only by the inherentreactivity of its electrophilic derivative but also by the balance between metabolic activation andinactivation reactions.5 (Table 2)

|

Table 2: Harmful effects of tobacco constituents

Click here to view |

Benzopyrene, the primary constituent of tobaccois metabolized by the product of P-450 gene, CYP1A1. Light smokers with the susceptiblegenotype CYP1A1 have a sevenfold higher risk ofdeveloping lung cancer, compared with smokerswithout the susceptible genotype. So, variations inthe activation or detoxification of carcinogens playan important role in the causation of cancer bytobacco products.6

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons andbenzopyrene are mutagenic and results in malignanttransformation of a lesion. Their primary target isDNA and the important genes include commonlymutated oncogenes and tumour suppressors suchas RAS and p53.4

When oral mucosa is continuously affected bytobacco carcinogens, unrepaired alterations in theDNA of mucosal epithelial cells occur which is thefirst step in the process of initiation. Inorder toinherit the change, the damaged DNA templatemust be replicated. Thus, carcinogen-altered cellsmust undergo atleast one proliferation cycle to fixthe change in DNA.3, 5

Initiation is followed by promotion andpromoters are the agents which donot causemutation but stimulate the division of mutated cells. Nicotine and phenols in tobacco act as promoterswhich are nontumorigenic by themselves, butaugment the carcinogenicity of benzopyrene andpolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (initiators). Promotion includes multiple steps such asproliferation of preneoplastic cells, malignantconversion, and eventually tumour progressionwhich finally results in oral cancer.6

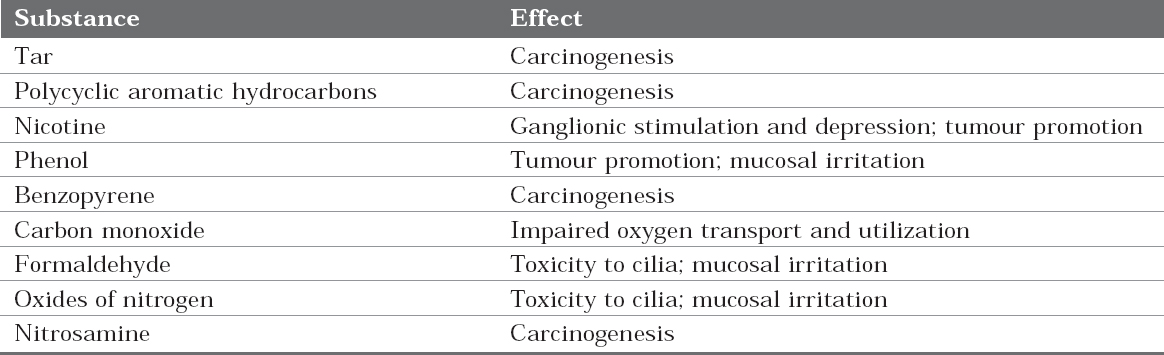

Tobacco, during the process of carcinogenesisattack the oral mucosa and results in variousdiseases and lesions depending on the type of tobaccoproduct used, type of habit and duration of exposure. The lesions included are listed in Table 3.

|

Table 3: Tobacco induced lesions

Click here to view |

Leukoplakia

In 1978, WHO defined leukoplakia as a whitepatch or plaque that cannot be characterizedclinically or pathologically as any other disease.7Later in 1984 at International seminar at Malmo, leukoplakia was defined as “A white patch or plaquethat cannot be characterized clinically orpathologically as any other disease and which is notassociated with any physical or chemical agentexcept the use of tobacco.8 The clinical types ofleukoplakia are (1) homogeneous (2) ulcerated (3)ulcerated with pigmentation (3) nodular (4) speckledand (5) verruciform.1

Smokeless tobacco induced lesion is found to bemore prevalent than leukoplakia mainly because thehabit of taking smokeless tobacco is more commoncompared to smoking. Even it requires longerexposure with smoke to develop leukoplakia thansmokeless tobacco induced lesion as it developsrapidly due to continuous local irritation by theplacement of betel quid.9 Leukoplakia is alwaysassociated with smoking habits only and it wasproved by many studies.10 Among all the smokinghabits, bidi smoking was found to be most prevalentin Indian population.1

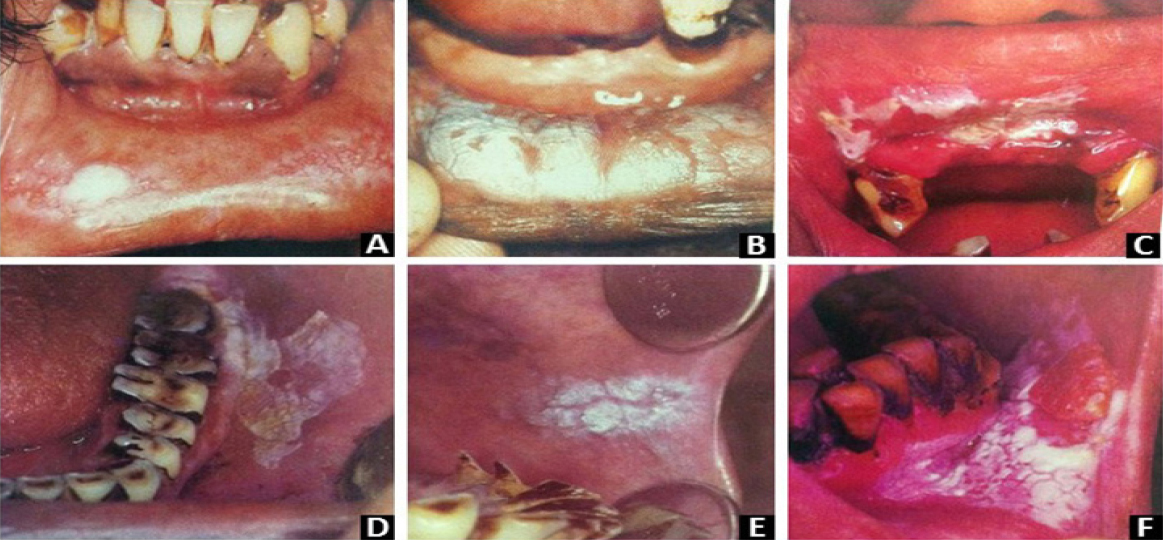

Leukoplakias associated with a smoking habithave a better prognosis compared to those notassociated with a smoking habit as after smokingcessation, most of the smoking-related leukoplakiaswill disappear.11 Clinically, smoking inducedleukoplakias are characterised by fine white striaethat imitate a fingerprint pattern in the mucosa. So, the lesions are referred to as fingerprint lesionsor a pumice stone type of lesion which possiblydisappear upon tobacco cessation and are generallyconsidered as non-premalignant.12 There is a site andtobacco habit relationship in leukoplakia (Figure 2).1

|

Figure 2: Leukoplakia: clinical types based on tobacco related habit (A) Lesion in individuals smoked till last ’butt’ remains (B)homogeneous leukoplakia-delicate white keratinized pattern in a hookli smoker (C) Thick homogeneous leukoplakia - mishri use (D)Leukoplakia - betel quid chewer (E) Homogeneous leukoplakia cracked mud appearance - beedi smoker (F) Homogeneous leukoplakia- khaini user. (From Fali S. Mehta, Hamner JE. Tobacco related oral mucosal lesions and conditions in India. A guide for dentalstudents, dentists and physicians. Basic dental research unit. Tata institute of fundamental research.1993, Bombay.)

Click here to view |

Leukoplakia on buccal mucosa: It is seenin individuals who smoke until only the small “butt”of cigarette remains.

Hookli associated leukoplakia: The stem ofhookli becomes hot when smoked causingleukoplakic lesions on lower and upper labialmucosa. These lesions usually have a delicatekeratinized appearance.

Mishri associated leukoplakia: Mishri is aroasted powdered tobacco popularly used forapplication over teeth and gingiva. These lesionsoccur most often on labial mucosa and gingiva. Theassociated lesions are thick and extensive, faint andsmall.

Homogeneous leukoplakia on labial commissure: It is most common in beedi smokers

Ulcerated leuoplakia: It is most common incommissure areas.

Khaini associated leukoplakia: Theselesions are usually thin and white with cracked mudappearance occurring most commonly in premolarregion of the buccal mucosa. Nodular leukoplakiashows higher risk for malignant transformation.1

In leukoplakias, the histopathologicalmanifestations were mainly in the form ofhyperparakeratinization and hyperorthokeratinization independent of theirclinical variants excluding verrucous leukoplakiawhich presents predominantly withhyperparakeratinization with parakeratin plugging. Other features include acanthosis and variousgrades of dysplasia.7

Palatal changes in reverse smokers

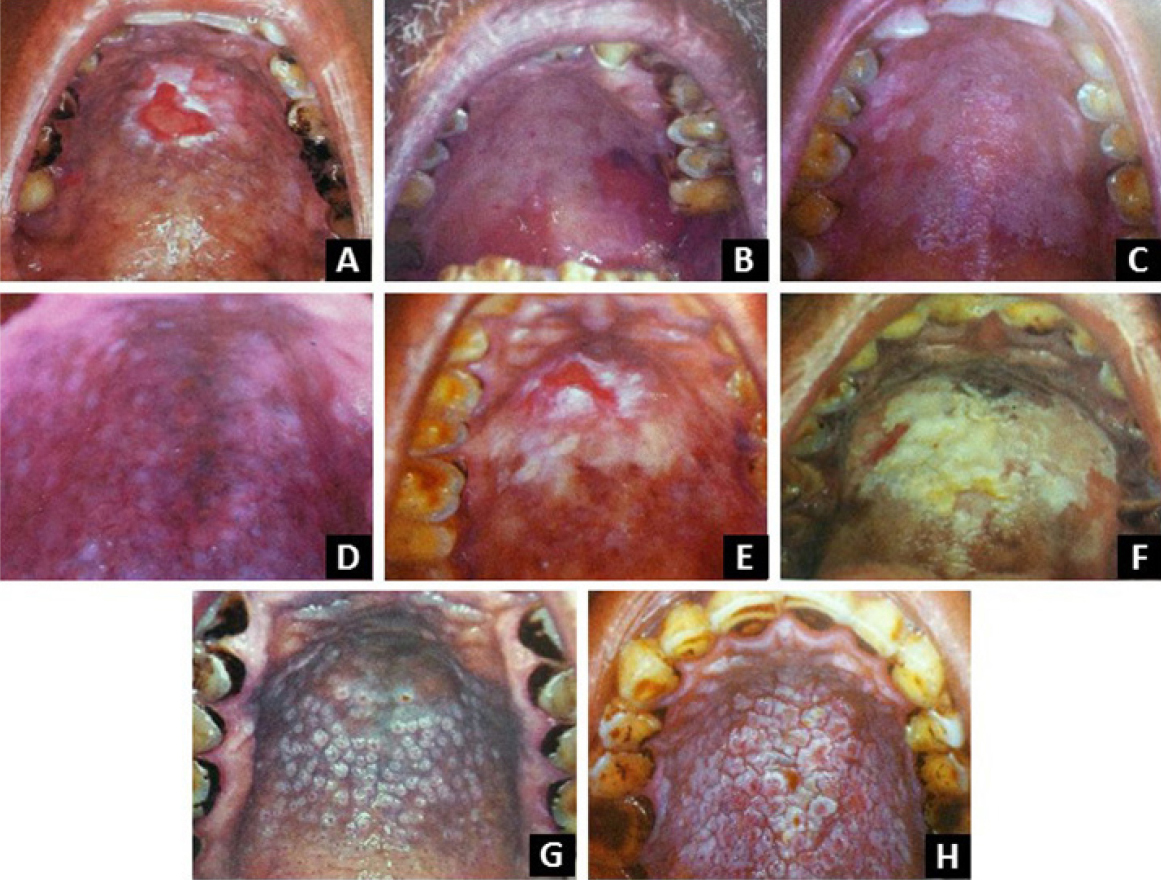

Reverse smoking evokes diverse alterations in thepalatal mucosa which can be of various patterns suchas palatal keratosis, excrescences, patches, red areas, ulcerations and pigmentation changes (Figure 3).1

|

Figure 3: Palatal changes in reverse smokers (A) Ulceration with peripheral keratinization (B) red areas (C) palatal keratosis(D) pigmentation (E) non pigmented area (F) palatal patch (G) excrescences (E) multimorphic palatal lesion showing excrescences andpatches with fissuring. (From Fali S. Mehta, Hamner JE. Tobacco related oral mucosal lesions and conditions in India. A guide fordental students, dentists and physicians. Basic dental research unit. Tata institute of fundamental research.1993, Bombay.)

Click here to view |

(1) Palatal keratosis presents as diffusewhitening of palatal mucosa. (2) Excrescences are1-3 mm elevated reas, with central red dotsrepresenting the orifices of palatal minor salivaryglands. (3) Patches are well defined, elevatedplaques. (4) Red areas are well defined reddening ofpalatal mucosa. (5) Ulcerated areas are crater likeulcerations with deposits of fibrin surrounded bykeratinization. (6) Hyperpigmentation is a protectivereaction to heat and smoke from tobacco. (7)Nonpigmented areas denote areas devoid of melaninpigmentation. Loss of pigmentation renders oralmucosa more vulnerable to action of carcinogens intobacco.1

Snuff dippers lesions

According to Hirsch et al, in snuff users therewill be higher incidence of keratinized lesions, sialadenitis and slight dysplasia.2 The oral mucosareacts to snuff by inducing hyperplasia in the basalcell layers and lethal damage in the surface layers. Juxta-epithelial band of sulphatedmucopolysaccharides (GAGs) is usually seen as astromal reaction to external damage by the snuff. The salivary glands and excretory ducts exhibitsdegenerative changes. Sialadenitis is more commoncompared to pathological changes in mucosalepithelium. The loss of salivary gland functions leadsto a decreased production of saliva and hencedecreased protection of the epithelium against snuffand other exogenous factors.2

Smokeless tobacco contains high concentrationsof calcium, which promotes epithelial differentiation;perhaps the calcium levels in the oral cavity leadsto the keratinization of normally nonkeratinizedmucosa. The increased keratin thickness may be dueto increased keratinocyte proliferation, decreasedcell shedding in the keratin layer or both.13 Murrahet al demonstrated that tobacco components arecapable of stimulating this proliferation.14

Nicotinic stomatitis

Also called smokers palate as it most commonlyoccurs on the palatal mucosa. It was named asstomatitis nicotina by Thoma in the year 1941as thelesion is frequently reported in tobacco smokers.15Pipe smokers and the individuals with reversesmoking habit develop this lesion most oftencompared to cigarette and cigar smokers.16Depending on the smoking habit and duration, theheat released attacks the palatal mucosa and minorsalivary glands and produce the characteristicclinical picture. Hard palate turns gray to whitecoloured depending on the amount of smoke. Scattered raised areas are ususally present with redcoloured centers. Raised areas are formed by theclumps of minor salivary glands and their ductopenings are seen as red dots because they donotkeratinize instead the entire palate undergokeratinization and appears white.17 It does nottransform into malignancy as it is a response to theheat of tobacco smoke rather than the chemicals. Itis completely reversible within a few months ofquitting the smoking habit.16

Oral submucous fibrosis

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic, potentially malignant disorder of oral mucosa whichwas first described by Scwartz in 1952.18 The majoreffect of this disease lies in its inability to open themouth and possessing the highest malignanttransformation rate which accounts to about7-13%.19 The Etiopathogenesis of OSMF is muchmore complex and involves multiple factors such asconsumption of chillies, nutritional deficiencies, betel quid chewing, genetic susceptibility, alteredsalivary constituents, autoimmunity and collagendisorders.20 Above all, betel quid chewing with orwithout tobacco constitutes a major risk factor.21 Allthe betel quid components have their individualeffects on oral mucosa either directly or indirectly. Areca nut is the important and main ingredientwhich affects the oral mucosa. Areca nut containsareca alkaloids such as arecaidine, guvacoline, guvacaine. Among which arecoline is the maincausative agent which is responsible for fibroblastproliferation. In the presence of slaked lime(Ca(OH)2), arecoline hydrolyzes to arecaidine whichstimulate fibroblasts and causes elevated collagensynthesis. Areca flavonoids such as tannins andcatechins cause increased fibrosis by forming a morestable and non-soluble collagen structure byinhibiting collagenase enzyme activity. Studiesshowed that there is 1.5 fold increase in collagenproduction by OSMF fibroblasts and as the diseaseprogressed type III collagen is completely replacedby type I.22

In a normal tissue, collagen is degraded byphagocytosis whereas in OSMF, arecolinesuppresses T cell activity which in turn decreasesthe cell mediated immunity resulting in decreasedphagocytosis.23

Copper present in the areca nut causesupregulation of lysyl oxidase enzyme whichincreases crosslinking of collagen and elastinmolecules. The enzyme levels increases duringfibrogenesis in OSMF.24 Areca nut acts as anexternal stimuli and induce OSMF by increasing thelevels of cytokines in the lamina propria and alsothe production of cytokines by peripheralmononuclear cells. The literature shows that OSMFsusceptibility could be cytokine based i.e., theyincrease the genetic susceptibility of OSMF patientsresulting in more penetration of arecoline andarecaidine into the oral mucosa.25

Lime which is a major component of betel quidcauses change in oral cavity environment fromneutral to alkaline. Under alkaline conditions, arecanut ingredients release reactive oxygen species(ROS). At ph>9.5 areca phenols (tannins andcatechins) undergo auto oxidation to releasesuperoxide radicals and H2O2. These ROS thenreacts with DNA and causes modification ofnucleotide by forming 8-hydroxydeoxygaunosinewhich leads to the formation of mutated initiatedcells during replication. This finally leads tomalignant transformation of OSMF.26, 27

Smokers Melanosis

Smoker’s melanosis is a brownish discolorationof the oral mucosa. Cigarette smokers usuallypresent lesions on the mandibular anterior gingivawhereas the pipe smokers on the buccal mucosa. Reverse smokers (people who place the lit end of acigarette into the oral cavity) present normally thepigmentation of hard palate. Smoker’s melanosisincreases with age which suggests that the longerthe person smokes, the more likely he will developthe condition. Nicotine (a polycyclic compound) isan important constituent of tobacco smoke whichmay be the main cause of smokers melanosis. Nicotine acts on melanocytes located along the basalcell layer of the lining epithelium of the oral mucosaand directly stimulate them to produce moremelanosomes. This results in increased depositionof melanin pigment as basilar melanosis withvarying amounts of melanin incontinence.28 AndersHedin conducted study to evaluate frequency andextension of melanin pigmentation in the attachedgingiva and its relation to tobacco smoking. Heconcluded that smoker’s melanosis is considered tobe caused by tobacco smoking and is expected to befound in other parts of oral mucosa.29

Oral cancer

The highest relative risk for cancer due tosmoking is the lung followed by larynx and oralcavity.30 The risk of oral cancer has increased inrecent decades in many countries in the world. Several studies evidenced that oral cancers are theresult of mutagenic events (arising mainly fromtobacco and alcohol) causing multiple moleculargenetic events in many chromosomes and genes. Theeffect of this chromosomal (genetic) damage is theimpairment of cell regulatory processes which leadto acquired capabilities within cells such as self-sufficiency in growth signals, insensitivity to anti-growth signals, evading apoptosis, limitlessreplicative potential, sustained angiogenesis andtissue invasion and metastasis.31

As already discussed, Two main carcinogenspresent in tobacco smoke are benzo(a) pyrine andtobacco smoke derived nitrosamines (TSNA). Theseare primarily metabolised to their activatedmolecules by cytochrome P450 andtheseintermediates are detoxified by glutathioneStransferase (GST) to hydrophilic and non-toxic GSTconjugated substances.32 Genetic polymorphisms inthese metabolising enzyme systems (CytochromeP450 and GST) and the resulting variants explainthe susceptibility to cancer in various organs. Ifdetoxification fails, then the metabolically activatedtobacco products would adduct to DNA and formDNA adducts. The DNA adducts associated withtobacco smoking provides a marker of thebiologically effective dose of tobacco carcinogens andassists in individual cancer risk prediction.33

CONCLUSION

Dental professionals are ideally placed for earlydetection of oral lesions associated with tobacco use, not only because the primary focus of the dentalexamination is intra oral but also because patientsare seen on a regular basis. Thus, detection oftobacco-associated lesions needs an adequateknowledge regarding the pathogenesis underlyingeach lesion. A proper diagnosis of lesion inconjunction with tobacco-use counselling by dentalprofessionals has become the standard of care.